Cet article a été rédigé pour la revue americanaffairsjournal.org

“With strong roots, plants will grow. With right approach, people will succeed.”

Yang Jiechi, Director of the CPC Central Foreign Affairs Commission Office, July 2018

The grand design came in 2013 from President Xi Jinping himself.

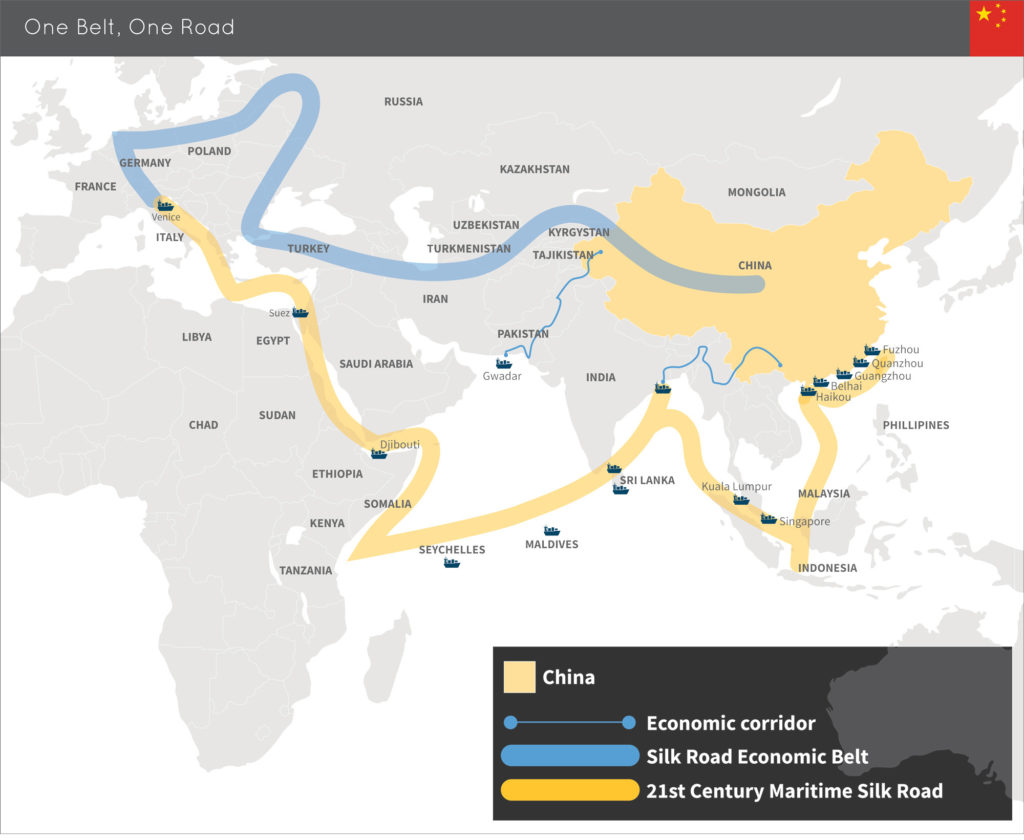

The goal was to launch the project “One Belt One Road,” or OBOR, across and around Eurasia, and to ensure mutually beneficial cooperation among all participating countries. At the time, the announcement of OBOR received little if any attention from European observers, distracted as they were by the difficulties of emerging from the euro crisis and the foreign policy challenges of Iran and Russia.

But turning a blind eye to China’s projects was never a worse idea. During the last five years, thousands of miles of railways have stretched from east to west across the European continent; millions of tons of concrete have been poured; some 4,500 high-speed trains have been constructed in China; deep-sea harbors have welcomed containers from China, and the battleships of the Chinese People’s

Liberation Army as well, in places where they had never been seen before. Thousands of companies, from Turkmenistan to Ireland and from Germany to Serbia, came to see the OBOR project as a major opportunity for trading and development.

AT THE HEART OF THE EURASIAN PROJECT

The first Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation hosted by President Xi in May 2017 attracted participants from 140 countries and 80 institutions—because it was, quite literally, on the way. Sixty countries actually have participated in the project, developing increasing links towards China, but also toward other Eurasian countries on a subregional scale. Some amazing results have already been achieved: in Uzbekistan, for instance, it used to take four or five days of difficult driving across rough mountain passes to travel by land from the capital Tashkent to the Andijan region, where about one-third of the population lives. But Chinese construction firms found a way under the mountains and helped build a railway tunnel in just nine hundred days. It is now an easy four-hour trip between the capital city and the Andijan province, according to Le Yucheng, China’s vice minister of foreign affairs.

In Henan province, the cradle of China’s empire and civilization, cities like Zhengzhou and Luoyang have been transforming at this breathtaking pace for decades, from provincial cities laden with memory to new Eurasian hubs with tremendous dreams. I was there at the end of October, on the invitation of the Chinese Embassy in France.

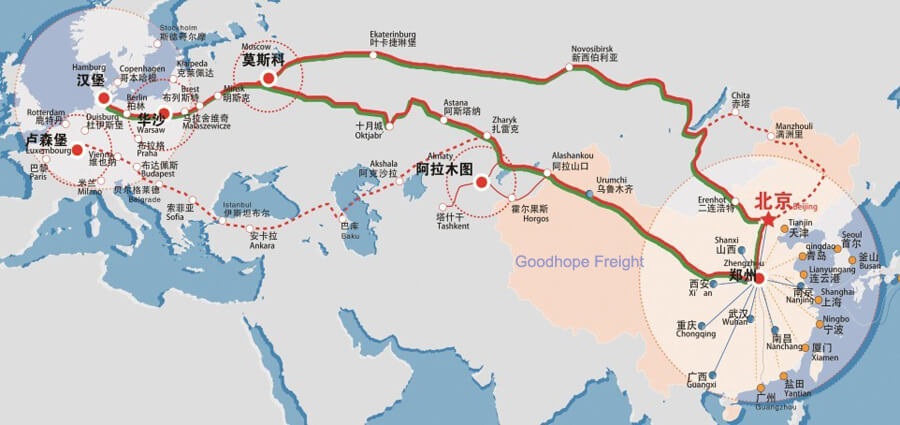

Zhengzhou is one of the most ancient cities of the Henan region, the heart of the central plain, whose nearly ten million inhabitants, five years ago, made their city one of the main ports of entry on the Silk Road at the request of President Xi Jinping.1 At the railway terminal of Zhengzhou in the China (Henan) Pilot Free Trade Zone, one freight train leaves for western Europe every day, and one arrives from western Europe—from as far away as Liverpool or Luxembourg. (The online trading platform for Zhengzhou-Europe unit trains started operations in December 2015; the regular operations of the cross-border e-commerce platform began opera-tions in January 2016.)

In the gigantic automated warehouses where samples of anything coming from the west are stored, one can find boxes of milk for children from Ireland, cheese and gifts from the Netherlands and Italy, mechanical tools and supplies from Germany, wines and gifts from Serbia and Georgia (French wines are, by some extraordinary privilege, strictly limited to Cahors). A strong sense of a new geopolitical unity impresses itself on anyone who watches, on a giant screen, the two railroad networks coming from Liège, Cologne, or Berlin, either by way of Poland and Smolensk on the northern route, or across Bucharest, Baku, and Almaty by the southern. Outside, thousands of Chinese-made cars are awaiting the next train, sandwiched between the buses and tractors that are inter-nationally acclaimed specialties of the city’s factories (Yutong is a well-known brand of buses, even in western Europe).

The freight using the railways is just a small part of the six trillion dollars of trade between China and other participating countries. But rail freight transport is increasing at a fast pace, and for an obvious reason: it takes just six to eight days for the freight to cross the Eurasian continent by rail, while it takes up to three weeks to travel by sea, and even longer from the far hinterland of Eurasia. Reaching a deep-sea harbor from the heartland is easier said than done, after all. Railway is better suited for perishable goods, in limited quantity, and much more flexible than some of the mon-strous container ships. And it offers an opportunity for small and medium-sized enterprises to reach the Chinese market at a low price; thus far freight has come abundantly from China, but less so from western Europe to China.

Of course, with hard infrastructure like railways, tunnels, and roads comes considerable soft power. The Confucius Institutes are never far from Chinese investments, and neither are diplomats and scholars. Banks and investment funds closely follow on the new Silk Road. Chinese investments in OBOR-participating countries rose to seventy billion dollars in 2018, and the Chinese development banks claim that more than two hundred thousand jobs have been created. Chinese authorities have also emphasized the new opportunities opened by OBOR for countries in search of partners. Rather inter-estingly, Germany is by far the chief partner of OBOR in western Europe, with a contribution of about 21 percent to this trade, while Great Britain and Italy are doing well with about 11 percent each. France, by contrast, lags far in the distance, comparable to Serbia or Switzerland, each at about 2.5 percent.

Railways, highways, and airports, mainly to western Europe, are intended to be one aspect of the project. A second set of connections may be even more exciting. Also known as the String of Pearls, it effectively encircles India—and a little bit more. Africa and even Latin America are considered legitimate parts of the Silk Road Economic Belt.

One Belt One Road thus forms an unlikely memorial to, of all things, the first giraffe to reach the Celestial Empire— which came from Mombasa in the fourteenth century, carried by one vessel belonging to the flotilla commanded by the great admiral Zheng He—which was considered a blessing from the gods to the emperor.

Visiting Sri Lanka, as I did three years ago during Maithripala Sirisena’s successful presidential campaign against the Chinese-aligned candidate Mahinda Rajapaksa (also supported by India), one could not but be impressed by the ubiquity of Chinese activity, especially near the deep sea port of Hambantota, eighty kilometers south of the capital city, Colombo. But more is to come. Mainly designed by the Chinese, a huge new port area called Port City, with some 2.6 square kilometers taken right from the Indian Ocean, is on the way in the heart of Colombo, across from the historic Galle Face Hotel. An estimated influx of eighty thousand people is expected in the next five years, along with the biggest foreign investment ever in the troubled Sri Lankan economy. How Sri Lanka will repay the loan is another question—and a question for Pakistan, Afghanistan, and many others.2

The port will offer a new hub for the Indian Ocean, for those ships which don’t want to go up north to the other major Chinese harbor, under construction in Pakistan. And let us go west. For the sake of fighting piracy, the Chinese army took a strong hand in the area near Djibouti, positioning both naval and ground forces there, and with a sharp eye to the fishing rights in the prosperous waters of the Red Sea. In addition, Djibouti is close to handing over to China the Port of Doraleh, giving it its first base in the Red Sea (as John Bolton correctly pointed out in a speech given to the Heritage Foundation on December 13, 2018).

Some agreements are said to have been signed with Sudan and Eritrea as well. In the deep south, China is actively working on Mozambique’s canal (with Mauritius and France’s Réunion territory in sight), but mainly seeking the natural resources of Madagascar— rosewood, palisander, and other precious wood, taken directly from what is left in the formerly magnificent “national parks.”

In western Europe, Chinese ships have a safe harbor in the Greek port of Piraeus—one of the little-known “successes” of the debt crisis managed both by the European Union and the IMF. On the request of its creditors, the heavily indebted Greek government had to sell some of the most valuable assets of the country, and guess who was a convenient buyer? A similar scenario is about to reach a happy end with a heavily indebted Italy dealing some of its ports and facilities to Chinese investors: a general agreement is supposed to be reached soon, on the request of Luigi Di Maio, Italy’s deputy prime minister. For the same reasons, Portugal was about to sell its main phone network to Chinese investors. China is widely seen as an excellent ally in the quest to push out an invasive and uncompro-mising European Commission.

To the north, the Chinese naval forces are actively working on the northeast passage, a reason why they have taken so much interest in Ireland and Denmark.3 Add to this landscape the building of a second Panama Canal across the equator—designed, financed, and built by Chinese companies—and the big picture comes into view: as the United States is beginning its strategic pivot to Asia, China is beginning its pivot to the world. China’s navy is even becoming a part of the Mediterranean playground. Just ten years ago, who could have predicted that?

All these deep-sea harbors and logistics platforms leave a huge physical footprint on local and regional economies and populations. The financial footprint is significant, as well. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor represents loans and investments of some $62 billion. For many countries of eastern Europe and central Asia, China has recently become both the first investor and the first lender.

Serbia and Azerbaijan are among them, with numerous worries lingering about their ability to service the debt, or whether they might have to sign over national treasures—mines, factories, fertile land—to pay the debt. In a few years, both the China Development Bank and the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the Russian-led Or-ganization for Central Asian Cooperation have taken a very strong position as a regional alternative to American-led international institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

In addition to these financial and industrial imprints, there is an increasingly significant digital one. The Silk Road is a strange animal, with at least three legs—and the third leg is the soft power arising out of the other two. OBOR comes with common rules and systems to make things work smoothly all along the railways, highways, harbors, and airports of the Silk Road. It comes with common rules to manage, secure, and dispatch the freight; common rules to organize traffic, signals, and logistic conveniences; and common rules for teams of workers making things happen—from drivers to road contractors to tunnel diggers.

It comes with Chinese security officers, lawyers, engineers, and designers embedded in the local teams of their counterparts. It comes also with the Chinese language spreading along the way, with Confucius Institutes following the Silk Road’s great opening, with the spreading of the “Chinese Dream” for the century, and also with contracts and agreements according to Chinese legal practices and behavior. Along with this soft power, a “digital Silk Road” is being built—the use of Chinese protocols, Chinese algorithms, and Chinese data centers, as well as cellphones from Huawei or ZTE, servers from Alibaba or Tencent, and financial and banking platforms managed from China with the renminbi as the new standard. This global design is, for better or worse, one of a ubiquitous China—a new China whose own playing ground is the world itself.

One of the most impressive pictures of the “Chinese dream” came to me during my first visit to the Shaolin Monastery, where some sixteen thousand students were training in the strictest fighting discipline of kung fu. A very strong mix of ancient culture, old martial techniques, and new management and educational tools mixed together to shape an indomitable commitment to win. For a Western observer, it is not insignificant that many religious devotees of the old Chinese fighting disciplines exercise every day with the top members of the PLA Special Operations Forces.

NEW VISION OR OLD EMPIRE? THE STAKES FOR EUROPE

Something larger is also happening at the heart of the Eurasian continent: it is the first time since the great invasions of the Mongol Empire, and after them the Muslim Caliphate, that land routes are open for trade between the Far East and the “far west” of Europe.

The extraordinary trips of Giovanni da Pian del Carpine or Marco Polo between western Europe, the Mongol tents, and China could not have been achieved after the fourteenth century. By that point, Muslim rulers had cut the land routes to the infidels and firmly established, for four centuries, a trade monopoly on the old Silk Road.

Those who favor the geopolitical strength of the Eurasian continent have strongly emphasized the global benefits of a project which aims to give Europe the means of its independence against the so-called puissances de la mer—the powers of sea trade, Great Britain and the United States. Sir Halford Mackinder wrote some decisive essays on the opposition between “heartland” and “rimland,” and it is clear that the twenty-first century has not forgotten these geo-graphical issues. They are back, with unexpected consequences.

Till now, the project has been about trade and development. But everyone can see the geopolitical issues playing out behind the curtain. OBOR could be a project of closer relationship between all the participants, bringing along with it new perspectives for the European Union, the former Soviet Republics of central Asia, the Balkans, and, last but not least, Russia. Could it perhaps be a distant consequence of the fall of the Iron Curtain dividing Europe between its western and eastern parts? Could it not also be a kind of reaction to the “pivot to Asia” in U.S. foreign policy, so deeply felt in some

European think tanks and institutions, not least NATO?On a warm Sunday in late May 2017, a very confident Angela Merkel told an assembly of her party, “The times in which we could rely fully on others—they are somewhat over.”4 She is among those who are progressively turning their political hopes and expectations away from the western Atlantic zone to the eastern continental zone and, eventually, as far as the Pacific Coast. From sea to land, the shift of power is one of tremendous importance and of uncertainty.

OBOR’s potential to divide the West has long been underesti-mated, but that is a mistake no one can make any longer. And it is increasingly provoking criticism from the United States and its allies, from India to Great Britain. The future of the Eurasian continent is at stake now, and many more issues are subject to new questions.5

There is a vision behind One Belt One Road, and there is a will. There is an opportunity as well, created by the civilizational decay of the European Union and the emptiness of Western strategy. Because One Belt One Road works, it attracts partners. Furthermore, it rep-resents a real and consistent opportunity for European countries stuck in the “high debt, low growth” trap, and it is quickly growing.

Throughout the world, OBOR is a global network of multidi-mensional relations, and the informational dimension must not be underestimated. At the very heart of the project lies the goal of broadcasting a Chinese voice and making the Chinese worldview more palatable for the global community.

Taking in the whole picture, it becomes obvious that OBOR involves African resources and needs, and even South American ones, as well (just have a look at Chinese investment in Brazil). An indebted Zambia is close to selling its major state enterprise to China, to secure a $10 billion debt. The same is true for some other countries in Africa and eastern or southern Europe. China’s benevo-lence offers a welcome escape from the strict budgetary discipline of the IMF or, in Europe, German rule. A new global power is advancing softly but quickly behind the OBOR project and its increasingly global reach.

Facing such a project, what are the expectations, fears, and hopes of the main powers involved? The so-called trade war between China and the United States has attracted a lot of fears and threats since fall 2018, particularly after the United States temporarily im-posed trading bans on ZTE, along with the spectacular arrest of the CFO of the Chinese telecom giant Huawei in December 2018, under suspicion of breaking U.S. sanctions against Iran. The trade war sheds light on issues of growing concern for U.S. and other western government agencies: How can we deal with the new Chinese tech giants? How can we rein in European countries that are searching for new visions—and, perhaps, new allies?

Last November, former Treasury secretary Hank Paulson delivered a speech about the growing dominance of “supertech China.” He emphasized the digital leg of the Silk Road, which, he said, seeks to impose China’s cybersecurity standards in every participating country (for obvious reasons), and to softly introduce a kind of dependence on China’s interests and legal framework. He judged that the U.S. attempt to change China’s behavior in commercial practices and intellectual property had been a “miserable failure,” and warned about an “economic Iron Curtain” beginning to divide the world. He then advocated a “Cold War–style technology denial” strategy against China. (The amusing image that comes to mind in some European countries is that of the “Echelon” system and the NSA’s meddling in European internal affairs, even spying on Angela Merkel’s private phone.) It is interesting to observe that the usually shy chief of Britain’s MI6, Alex Younger, speaking at his old Uni-versity of St Andrews in early December 2018, gave British students the same message. He warned them about the use of Chinese-made electronic devices, even cellphones, and questioned the ability of Chinese providers to cope with the security requirements of the British government. He described the digital industry as a key used by China to enter banking, financial, and information networks and, at the end of the day, to influence the formation of public opinion itself.

The fear of a Chinese strategy aimed at global media dominance, widely spread by U.S. and British media, helps to inculcate in European and American citizens a certain hostility to China and to emphasize the threat coming from China’s soft and smart power push. It is all too easy to warn of the “yellow threat” in order to unite Western people in disarray against the craftiest enemy. For an outside observer such as myself, it is more than a little amusing to read so much about Chinese propaganda (and, of course, Russian propaganda) and so little about the U.S. propaganda machine, by far the largest in its class. And the threat now is widely seen as arising from the well-known Thucydides Trap—the inevitable conflict between a growing power and a declining power, like that between Sparta and Athens during the fourth century BC.

The prospect of commercial conflict, however, remains uncertain. Some European countries are following U.S. requests closely, al-ready closing their markets to Huawei or ZTE and putting up barri-ers to entry to Chinese money, Chinese goods, and Chinese high-tech services. They share the U.S. administration’s concern (and that of John Bolton in particular) that China and Russia’s push in Africa, central Asia, and even South America is undermining the national interests of Western countries. Nevertheless, the unilateralism of the United States can only be accepted with caution—especially when a strong assertion of European nationalisms is on the way, with loud acclaim from President Trump himself. More and more countries around the world will not be able to help experiencing American unilateralism as an aggression against their free will, a denial of national sovereignty, and a serious cause of global trouble. Another question will soon emerge, as well: does cutting relations with China and trying to isolate it mainly harm China or, given the present shape of the world economy, would it do more harm to the interests of U.S. and European corporations?

A NEW MODEL OF GLOBALIZATION

Today, the fate of globalization seems to be at stake, along with the end of the “easygoing” ideology behind it. These are troubling and confusing times for a lot of Europeans. Many have come to believe that the system of “no border, no tariff, no nation” has failed miserably. Some European countries have not yet recovered from the 2008 financial crisis. A growing number of European leaders, from the Brexiteers in England to Viktor Orbán in Hungary and Matteo Salvini in Italy, tell another story to their constituents.

According to them, the future will put an end to the fairy tale of globalism, free trade, and open-borders ideology. They repudiate globalism as a common hope; they see it as a common threat—the path to a new subordination and a step toward colonization. They mostly agree with Donald Trump that a country without borders is a vanishing entity, and that the price for free trade cannot be the free will of the people itself. They also agree that nationalism is the living force of free nations and that national interests will decide the future.

At the same time, other Western leaders, many in business and universities but also in the leading countries (like French president Emmanuel Macron), still stand firmly within the narrative of the 1990s—the triumphant globalist talk and the unbreakable faith in free trade and open commerce. They still imagine the future as it seemed in the not-too-distant past. They have been saying for many years that concern about the national origins of any product is ille-gitimate.

Everything is simply “made on earth by humans”; every-where, went the slogan, we can find “the same people doing the same jobs and searching for the same performance.” The digital age was supposedly driving everyone toward a borderless, limitless world. And from this standpoint, why should it be a problem to deal with China, and to welcome railway stations, harbors, and highways from the OBOR project? Why should it be a problem to buy China’s products and services, to borrow from Chinese banks, and to expect a better future benefiting from the Chinese demand for Western brands?

Yet, in a strange irony, some of the strongest defenders of globalization have become the most vocal critics of China’s growing willingness to reshape the world order. What will happen, they ask, if China wants to control or monitor companies—and even coun-tries—which have become dependent on China’s economic strength? What will happen if China uses its power to reshape global political institutions? They fear the return of geopolitics, of the struggle for power, influence, and wealth, and the disappearance of the world as an open market. This 1990s vision now seems inescapably trapped between Western “populist-nationalists” on one side and Chinese ambitions on the other.

Meanwhile, political confusion in the United States has not helped Europeans who want clear answers on free trade, transconti-nental relationships, and dealing with China. Unpredictability and uncertainty in U.S. foreign policy have left European leaders unpre-pared and unable to cope, especially vis-à-vis China. They felt oppressed by the “hyperpower” of the United States, but they are lost without it.

The heart of the issue lies here: from NATO to OBOR and the European Union itself, Europe has come back into history. Mercan-tilists or nationalists, federalists or populists, all of them seem to agree on one point: the European Union is engulfed in the end of “the end of history” and the fear of the end of the Union itself. They share a growing concern about the decay of existing international institutions, from the WTO to the UN, from NATO to the World Bank, each growing increasingly irrelevant though not definitively out of the picture.

The lip service paid by China to traditional institutions is not an answer: China both enforces its presence in all these institutions, and at the same time carefully builds institutions on its own initiative with close allies, which eventually could become strong pillars of a new world order—a Chinese one.

What will happen? It will be very surprising if some dramatic events don’t occur to interrupt, delay, or destroy some parts of the

OBOR infrastructure. In the current trend of growing tensions between the two superpowers, anything could happen. OBOR will increasingly become a divisive issue, one of intractable opposition and harsh judgments. We will witness both covert and open actions to prevent countries or companies from dealing with China and participating in the OBOR project, as well as covert and open operations to disrupt, delegitimize, and condemn any involvement in it. Land routes are very easy to close or at least to threaten. Every oil or gas company is well aware of the political risks facing any land pipeline. The same is true for railways, highways, even airports

“Accidents” may occur, and the threat of conflict, for instance in theBalkans or central Asia, cannot be dismissed.

This is a nightmare for European countries, heading toward a multipolar world and having to make a choice between dependence on the United States or colonization by China. Different pressures will affect the countries and companies most engaged with China’s network of trade, finance, information, and intelligence. Indeed, they already do. Would an isolated China be more disruptive? Or is growing global dependence upon China a greater risk?

Indeed, we are at the end of the former Western world as we know it. The world is not becoming another Europe, nor a global America. Something different is taking place. With all the know-how, tools, and technologies that they have acquired, mainly from the West, China is building something different. The old dream of the 1950s, “growth brings peace,” is irrelevant, mainly because of the massive impacts of economic growth on the environment. And it’s also irrelevant because China (along with India and Russia) is not becoming a new version of America.OBOR is but one expression of the coming new world order slowly emerging from the great confusion of the 1990s.

One cannot understand what is at stake without attending to geography, culture, spiritual needs, and the burning desire to say “We, the people.” The growing complexity of an architecture of local diversity, regional integration, and international multipolarity is gaining ground stead-ily against the fictitious trend toward global convergence and uni-formity. The question is how to manage both the diversity of human people, cultures, and civilizations, and the strong push from private, multinational corporations to flatten rules, regulations, tariffs, and all other practicalities of trade.

And on this point, globalization and democracy increasingly become antagonists. For European nations and for the European Union as well, the fear of accepting a new form of subordination is never far away, especially in those eastern nations which have experienced political freedom for less than thirty years.

Far beyond commercial interests, OBOR represents the seeming-ly forgotten figure of political self-assertion. It carries a vision rarely seen elsewhere. It seems to be a question of “to be or not to be” for many European nations disappointed by the lack of will and vision of their own union. The future of the West is at stake, and the debate is just beginning.

NOTES

- On Zhengzhou, see John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman, China: A New History, 2nd enlarged ed. (Cambridge: Belknap, 2006). The ZhengzhouInternational Hub Development and Construction Company Ltd. was established on June 27, 2013.

- Part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the Gwadar Port became operational in 2016. See Jean-Michel Valantin, “China and the New Silk Road: The Pakistani Strategy,” Red (Team) Analysis (blog), May 18, 2015.

- Linda Jakobson, “China Prepares for an Ice-Free Arctic,” SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security no. 2010/2 (March 2010).

- Alison Smale and Steven Erlanger, “Merkel, after Discordant G-7 Meeting, Is Looking Past Trump,” New York Times, May 29, 2017.

- Helen Wang, “China’s Triple Wins: The New Silk Roads,” Forbes, January 15, 2016.

0 commentaire